Dr. Jia-Sheng Wang

Though scientists have known about the potential dangers of PFAS, commonly called ‘forever chemicals,’ for decades, the Environmental Protection Agency only began to crack down on their use in products ranging from food packaging to cosmetics in 2021. Then, last summer, the EPA warned that PFAS may be even more dangerous to human health than previously thought, even in small doses.

In 2022, the EPA awarded over $7.7 million to support research projects at 11 institutions to develop new methods of measuring and evaluating the potential harms of PFAS. Faculty at UGA’s College of Public Health were among the teams to receive EPA funding.

For our latest explainer, environmental health science (EHS) researcher and department head Jia-Sheng Wang discusses the health impacts of PFAS and the aims of the UGA project, led by EHS faculty member Lili Tang, with support from Ye Shen, a faculty member in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics.

What do we know about how PFAS, also known as “forever chemicals,” negatively impact humans?

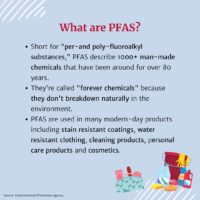

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of synthetic chemicals that have been widely used in industry and consumer products since 1940s. These human-made chemicals have a variety of functions, from making our kitchen pans stick-free to water-repellent fabrics for athletics. However, more studies are revealing their persistence in the environment and bioaccumulation inside of animal and human bodies. In addition, their links to many adverse health outcomes like cancer and dysregulation in the nervous system has alerted the scientific field, EPA and other federal agencies to the need for these chemicals and their mixtures to be the top priority of research and risk assessment.

What do we know about how individual chemicals can impact neurodevelopment?

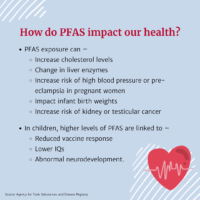

A great deal of data have been generated in last 20 years about the effects of environmental exposures on susceptible populations, specifically children. Children exposed to many chemical toxicants, such as heavy metals, pesticides, and PFAS chemicals, showed higher blood levels of these toxicants, which are correlated to lower IQs, abnormal gene expressions of neurotransmitters, and other impacts to neurodevelopment. Developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) is defined as the detrimental functional and structural consequences of chemical exposure on the developing nervous system of offspring that may occur during pregnancy and early life. These detrimental impacts include impairments in movement, learning, memory, and cognition. More cases of neurodevelopmental disorders in children have been observed and linked to pre- and postnatal exposure to PFAS.

Generally, what is your project seeking to do?

This project aims to develop a quantitative adverse outcome pathways (qAOP) network, a new model that can predict how toxic a chemical is to cell tissues at different doses, to assess the potential harms of PFAS and other mixtures to the developing nervous system using the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans). C. elegans which has a similar genetic make-up and whole-body design (e.g. skin, intestine, neurons) to humans. The rationale of the project is that although we know adverse health effects of single chemicals, environmental chemicals are often present as mixtures in the air, water, soil, food, and commercial products. There is an urgent need to assess the toxicity of chemical mixtures to understand their combined negative effects on animal and human health under different environmental conditions.

Results of this project will generate new scientific data and improve fundamental knowledge on DNT testing that has not previously been conducted in-depth for PFAS. And, the qAOP network we will be developing for this project will be useful for other mixture-based hazard and dose-response assessments, which offeres more tools to address chemical contaminants of concern and could improve local and state decision-making.

How will this project integrate into the work the Department of Environmental Health Science and Dr. Tang’s lab is doing now?

Dr. Tang’s laboratory has been focused on development of the high-throughput screening (HTS) platform in the C. elegans model for over 10 years. The HTS platform is the use of automated instruments to rapidly test hundreds and thousands of chemicals and chemical mixture samples to see how these chemicals are interacting with and potentially harming cells and other tissues, down to the molecular level. Her laboratory has used the HTS platform to understand the impacts of various environmental toxicants and to define the roles of microbiota in response to environmental toxicants, with special focus on carcinogenic and neurotoxic effects. Last year her laboratory received USDA NIFA research funding to use the C. elegans model system to explore the neuroprotective effects of compounds in tea on Parkinson’s disease. Data from these two funded research projects will be integrated to provide both sides of the environmental health research – adverse and beneficial effects of environmental chemicals.

Infographics created by Emily Loedding.

Posted on February 15, 2023.